How many times have you heard sceptics say something such as:

“If you did an MRI scan of most people without symptoms you’re likely to find evidence of painless dysfunction.”

OR

“If you scan people with painful symptoms you’ll often find no obvious dysfunction or abnormalities”

A 2011 study shows (at least part of) these statements to be superficially correct….so where does that leave manual therapists who ‘identify’ dysfunction by palpation and assessment methods – which they proceed to treat in order to modify symptoms (pain etc)

In a 2011 study, entitled ” Ultrasound of the Shoulder: Asymptomatic Findings in Men” Girish et al noted that when the shoulders of just over 50 asymptomatic men, average age 56 – were scanned, fully 96% showed abnormalities, ranging from osteoarthritis to labral tears and tendinosis.

The abstract reads as follows:

OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this study was to examine the range and prevalence ofasymptomatic findings at sonography of the shoulder.

MATERIALS AND METHODS. The study sample comprised 51 consecutively enrolled subjects who had no symptoms in either shoulder. Ultrasound of one shoulder per patient was performed by a musculoskeletal sonographer according to a defined protocol that included imaging of the rotator cuff, tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle, subacromial-subdeltoid bursa, acromioclavicular joint, and posterior labrum. The shoulder imaged was determined at random. The 51 scans were retrospectively analyzed by three fellowship- trained musculoskeletal radiologists in consensus, and pathologic findings were recorded. Subtle or questionable findings of mild tendinosis, bursal prominence, and mild osteoarthritis were not recorded.

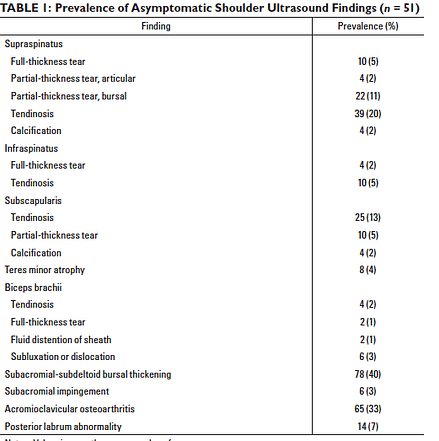

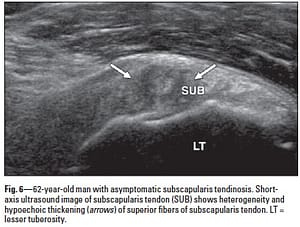

RESULTS. Twenty-five right and 26 left shoulders were imaged. The subject age range was 40–70 years. Ultrasound showed subacromial-subdeltoid bursal thickening in 78% (40/51) of the subjects, acromioclavicular joint osteoarthritis in 65% (33/51), supraspinatus tendinosis in 39% (20/51), subscapularis tendinosis in 25% (13/51), partial-thickness tear of the bursal side of the supraspinatus tendon in 22% (11/51), and posterior glenoid labral abnormality in 14% (7/51). All other findings had a prevalence of 10% or less.

CONCLUSION. Asymptomatic shoulder abnormalities were found in 96% of the subjects. The most common were subacromial-subdeltoid bursal thickening, acromioclavicular joint osteoarthritis, and supraspinatus tendinosis. Ultrasound findings should be interpreted closely with clinical findings to determine the cause of symptoms.

Examples of abnormalities identified, without any reported symptoms

Does this mean that we should conclude that ‘symptoms’ and ‘dysfunction/ abnormalities’ are unrelated?

I think not.

What it does suggest is that, as adaptation progresses, a threshold is reached where dysfunction/abnormalities start to produce obvious symptoms, whether pain or functional limitations.

It also suggests that many people have relatively high tolerance levels.

This reminds me of a phrase that I first heard used by Jeffrey Bland PhD, pioneer of nutritional medicine: “many people are “vertically ill” – they are not sick enough to lie down, but they are certainly not well” In other words – adaptation to stressors accumulate until breakdown begins and symptoms appear. This is true for most of us and is a clear demonstration of Selye’s ‘Adaptation Syndrome”

- General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)

- Local Adaptation Syndrome (LAS)

Both involve initial defensive (‘fight/ flight’) Alarm response to stressors. If stress continues an Adaptation phase (‘resistance’) follows, leading to a phase of Exhaustion (collapse, dysfunction, symptoms) (Selye 1956)

I would therefore challenge the researchers of the Girish article to define ‘asymptomatic’. In fact to an extent they address this in their concluding remarks, when they say:

There could be “recall bias of the patient sample with regard to the absence of previous symptoms.“….interpretation…..minor symptoms (functional restrictions? discomfort?) may not have been reported as they were so familiar to the individual that they have become part of everyday life.

AND

“A current absence of symptoms does not exclude the development

of symptoms“….. interpretation: ….its just a matter of time….!

Another thought is that a full functional assessment was not carried out to evaluate ranges of motion changes. For example in the very high levels of sternoclavicular osteoarthritis, it is hard to believe that scapulohumeral rhythm would be optimal. ….in other words, these changes were possibly not symptomatic, but they are certainly not ‘normal’.

My preference clinically is to try to relate dysfunction to symptoms, and to encourage – through better ergonomics, posture, patterns of use – a reduction in whatever stresses the system is adapting to…enhancing functionality, reducing adaptive load… a formula for improved self-regulation and well-being.

See previous posts on this topic:

https://leonchaitow.com/2011/11/13/776/

https://leonchaitow.com/2008/12/10/biomechanics-malalignment-and-adaptation/

https://leonchaitow.com/2008/01/28/adaptation-it-saves-us-and-it-kills-us/

References

- Girish G et al 2011Ultrasound of the Shoulder: Asymptomatic Findings in MenUltrasound of the Shoulder: Asymptomatic Findings in Men American Journal of Roentgenology 197(4) http://www.ajronline.org/doi/abs/10.2214/AJR.11.6971

- Selye H 1956 The stress of life McGrawHill N.Y.